Our recent road trip took us to the incredible Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle, and we were captivated by the strange, wonderful, and sometimes eerie history on display. We found ourselves face-to-face with four artifacts that tell a compelling story of old folk traditions, magical practices, and the people who believed in them.

The Unseen Protectors

One of the fascinating traditions we saw evidence of was that of concealed cats, believed to offer magical protection for a home. The museum has a pair of these mummified cats that were found under a front door in Bristol. This tradition speaks to a world where magical beliefs were a hands-on part of everyday life, offering a silent guardian against malevolent forces.

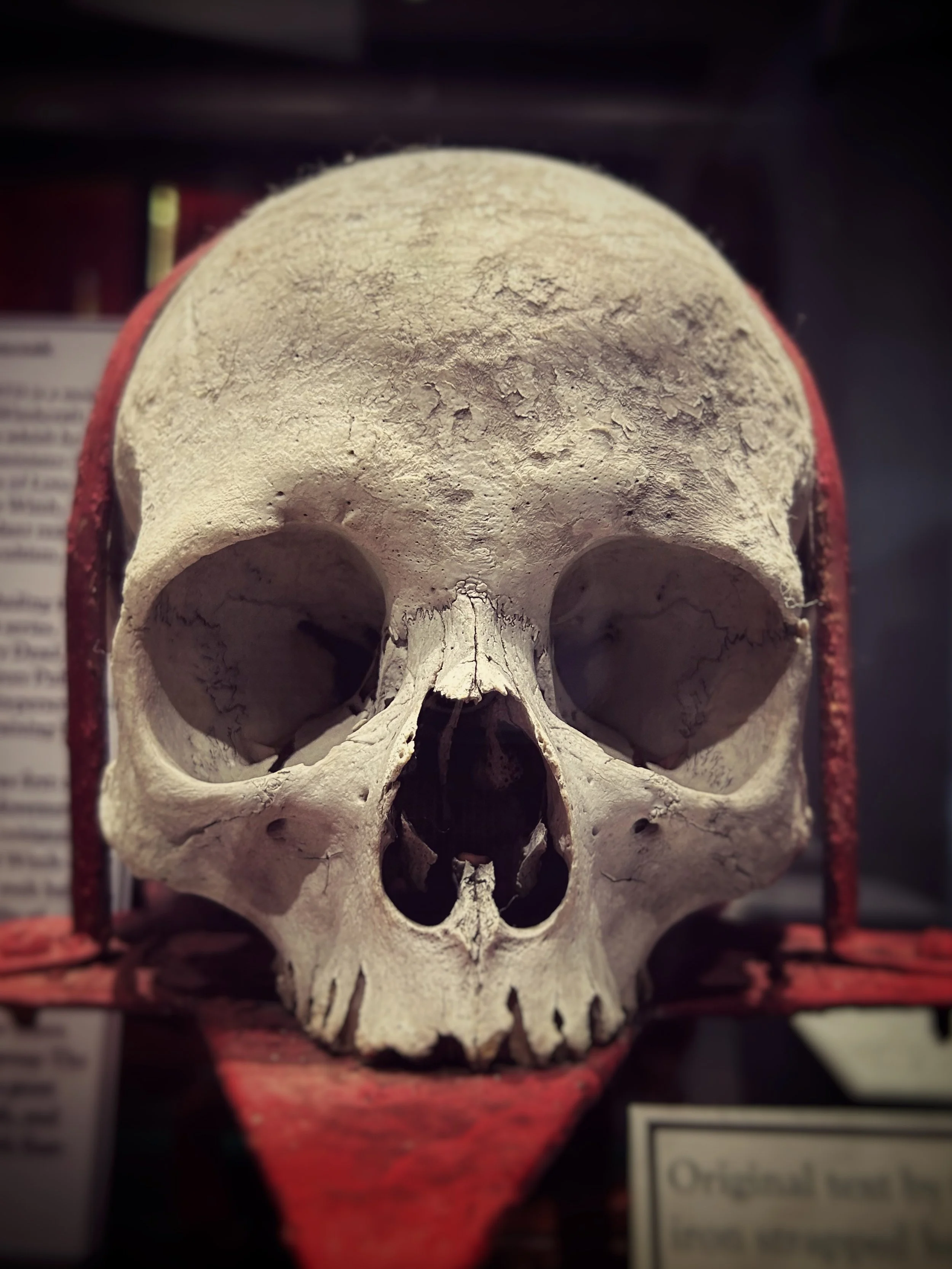

The Iron-Strapped Human Skull

Among the museum's most captivating artifacts is this iron-strapped human skull. According to Cecil Williamson, the museum's founder, it belonged to a wise woman from the north Bovey area who affectionately referred to it as “her friend.” She would tell her clients, “Well me dear, I don’t rightly knows what I a do - till I have asked me friend. I’ll let thee know later.” While the story of “Granny Mann” is a powerful piece of its history, we can’t help but wonder who this person was long before the skull became a tool for magic. The thought of this relic is both eerie and beautiful.

The Helmet of the King of Witches

Our visit also brought us face-to-face with a key piece of modern magical history: the ritual helmet that belonged to Alex Sanders, the “King of the Witches.” This incredible artifact was used by Sanders for many years and was adapted several times. Early photographs show it without horns, but in a well-known image on the cover of Stewart Farrar’s book, What Witches Do, it’s shown with straight horns and large feathers. Seeing how the piece evolved truly brings to life the hands-on nature of these magical traditions.

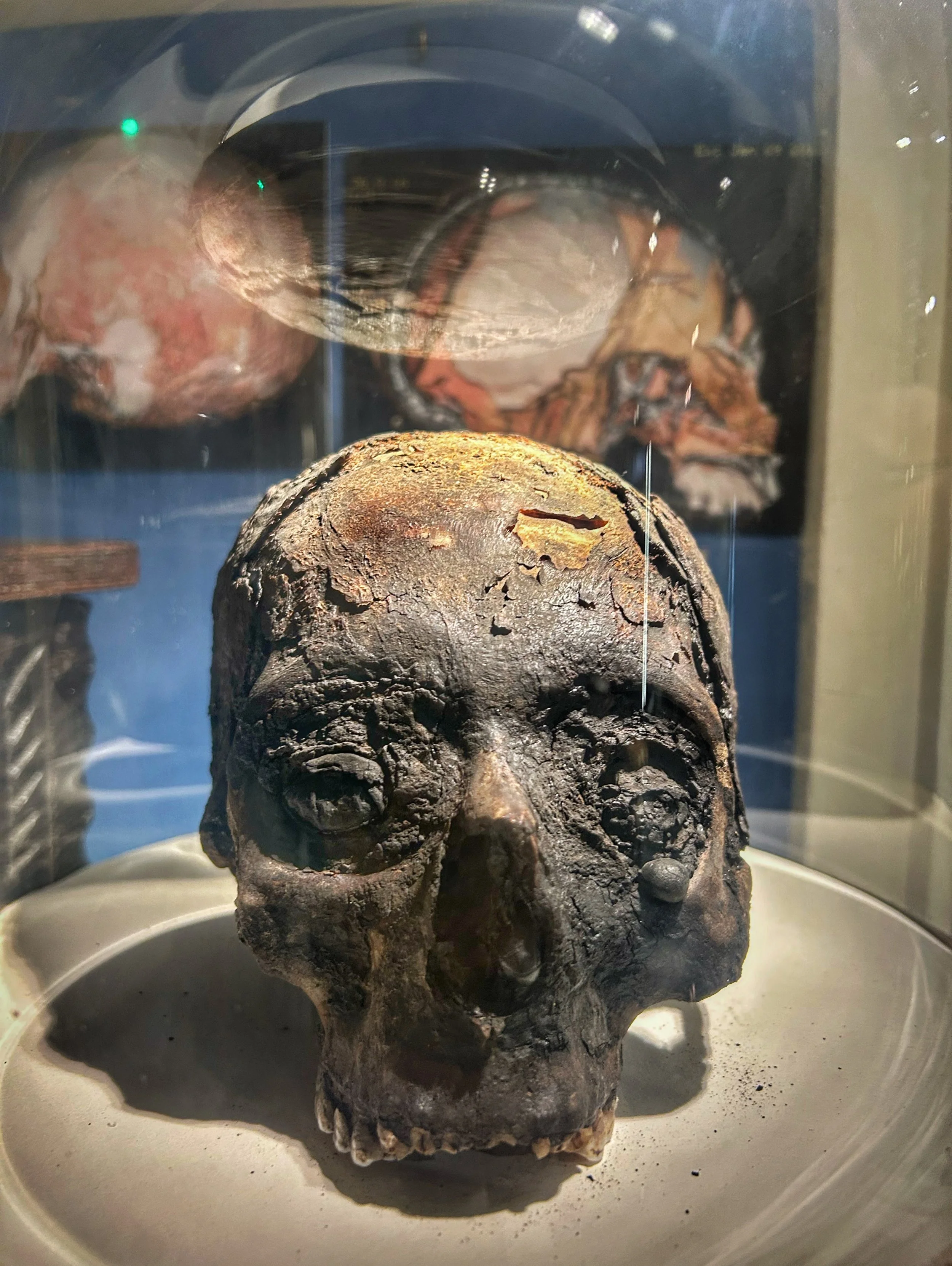

The Strange Case of Harriet

Perhaps the most unique find in the entire museum is “Harriet,” a tarred head that holds an incredible and poignant secret. Initially, she was thought to be a medieval saint or criminal, but forensic tests revealed a much more remarkable truth: Harriet was actually a female Egyptian, mummified with tree resins around 200 BC! Her head was likely stolen by treasure hunters, sold as a fraudulent relic to a European church, and eventually found in the rubble of a bombed-out London church during the war. Her journey through time and belief is a testament to the strange ways artifacts can travel. The exhibit text ends with a powerful plea, asking visitors to not dislike the head and to spare her a kind thought or smile—a poignant reminder that she was once a person who could laugh and cry like us.

These unique artifacts are more than just items in a collection; they are powerful testaments to the enduring nature of folk traditions and magical beliefs.